IQ: Institutional Quarterly

Intuition vs. computation: A brief history of quant investing

April 23, 2024

When joining BMO Global Asset Management, my first impression was one of familiarity. I met new team members and discovered new processes, but for the most part, the philosophy underpinning the Quantitative Investments team (formerly the Disciplined Equities team) was one that I shared deeply: that humans should collaborate with machines on investment decisions rather than rely on a “pure” quantitative approach. Experience had shown me—and my new colleagues—that a balance between intuition and computation was necessary to navigate the rigours of the market. History had shown it, too.

In the following report, we will explore the origins of quantitative investing and the evolution that has taken place to responsibly harness the powers of mathematical modeling, technology and human cognition.

An Opportunity for Academic Arbitrage

During the post-World War Two era, there was a minor renaissance taking place in academia. Researchers of all disciplines crossed traditional academic boundaries to explore subjects that had historically run parallel to their own. Biologists, for example, entered the world of physics; physicists experimented with the emerging field of computer science; and mathematicians investigated questions within finance and economics.

What they found was surprising—that although finance was often treated as a rigorous subject, it did not always behave like one. In many instances it lacked discipline, a mathematical backbone, which meant its hypotheses about the world were not always tested. Scientists saw this as an opportunity to import their quantitative skills and transform economic theories into clear, logical equations. In short, they saw an opportunity for academic arbitrage.

The new quantitative approach was often perceived to be in conflict with a more traditional investment style. For decades, the division would hold: fundamental analysts to one side, “quants” to the other. Only since the Great Financial Crisis have institutional investors come to realize that the relationship between the two need not be contentious; that, in fact, a strategic balance can be found to harness the strengths of both.

Key Milestones

More Than a Century in the Making

While scholars disagree on when in the twentieth century the first collision of math and finance occurred, there is no doubt that many academics were on that frontier. In 1900, a French mathematics PhD candidate named Louis Bachelier submitted a doctoral thesis on the movement of stock prices. Half a century later, future-Nobel laureates Harry Markowitz and Eugene Fama both made major strides in quantifying ideas on market theory and portfolio construction. They were all on the frontier, building the scaffolding of a new science to bring quantitative rigour to Wall Street.

A pivotal contributor, however, was Edward Thorp, a mathematician who used his knowledge of statistics to invent the idea of card counting in blackjack. Thorp actually went to Las Vegas with $10,000 of borrowed cash and more than doubled his money by the end of the weekend.1 Later, he invented a wearable device to predict where the ball would land on a roulette wheel. While illegal, his invention showed how someone could take a randomized problem and harness a disciplined approach to generate superior results.

Eventually Thorp turned his talents to finance. He founded the Princeton/Newport Partners—what some would consider the first hedge fund of its kind—and found near instant success1. But he wasn’t the only one experimenting with quantitative methods. In the late 1960s, Wells Fargo went outside its traditional hiring pool to bring in graduates from math and physics. Among them was a young man named Fischer Black.

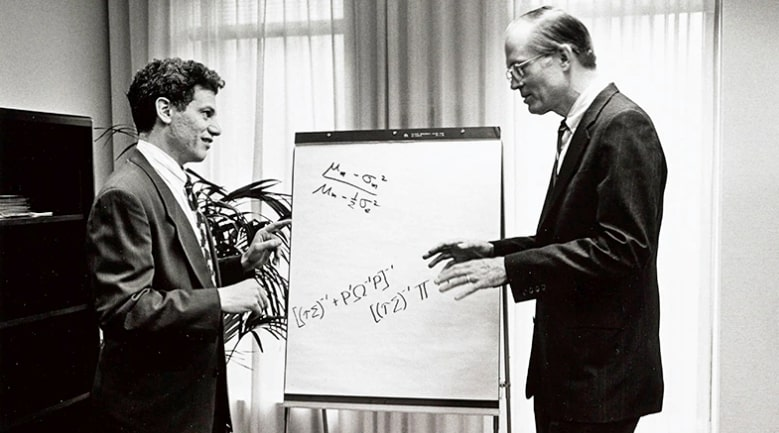

Robert Litterman and Fischer Black, 1994. Source: Goldman Sachs (Asset Allocation Model Is Developed at Goldman Sachs.)

Black, who held a PhD in Applied Mathematics from Harvard University, was a fish out of water on Wall Street. Despite finding a few like-minded individuals who believed that advanced modelling could improve investment returns, he left the private sector during the 1970s and returned to academic life at the University of Chicago.

His timing couldn’t have been better—a new options exchange had recently opened in Chicago, raising interest in scholarly work related to derivatives. Here Black found a practical application for his insights from Wall Street, and before long he co-authored the now famous Black-Scholes model for derivatives pricing. It made him an instant celebrity.

In fact, when Goldman Sachs was building its first ever Quantitative Strategies Group in 1983, they could have chosen a leader from any number of their internal staff. Instead, they approached Black—and he said yes.3

The Rise of Computing Power

Through the 1970s and 80s, Wall Street had the blueprints for mathematical models to help make their investment decisions—but not the technology to make them truly scalable.

However, once we entered the 1990s, computers were not only more powerful, but also less expensive and more easily available than ever before. In fact, between 1955 and 1990, computing power improved by a factor of one million.4

This meant that the ground was fertile for change. Consider the rapid progress: the World Wide Web was in its infancy at the start of the 1990s, yet before end of the decade, Google and Amazon had been established; at least 60%5 of the United States owned a computer; Steve Jobs returned to Apple and introduced the iMac; Napster launched peer-to-peer file sharing, nearly destroying the music business; and hedge funds experienced a massive boom in popularity.6

Between 1955 and 1990, computing power improved by a factor of one million.4

Unexpected Challenges for Quant Investing

That said, the journey of quant investing was not always smooth. In August 1998, the world was shocked by the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM)—a highly leveraged quant fund dealing in arbitrage trading and interest rate swaps.

The initial crisis was triggered by the Kremlin defaulting on its debt obligations. At the time, LTCM had been holding a large amount of Russian government bonds and the losses they incurred forced LTCM to liquidate other positions, which in turn led to further write downs and a “flight to liquidity.” It was a vicious spiral. Fear of contagion spread rapidly. So, to prevent a full-blown crisis, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York intervened with a US$3.75 billion bailout.

Russia defaulting on a bond payment triggered LTCM’s downward spiral.

After the LTCM dust settled, institutional investors continued to invest in quant strategies during the early 2000s. Greater and greater computing power instilled stronger and stronger belief in the power of machine-driven investing. However, institutional investor confidence was tested once more.

On August 6, 2007, some of the largest quant funds in the world sold their more liquid equity positions to cover losses in their illiquid holdings. This triggered a domino effect, where other pure quant funds unthinkingly followed suit, rotating their assets and driving equity prices down. Although prices stabilized within a week, the so-called “Quant Quake” had done its damage.

Markets confidence was shaken and money flowed out of quant strategies. Goldman Sachs’s Quantitative Investments Strategies team, which managed $165 billion at its peak, saw its asset base fall to a low of US$38 billion by 2012.8The conventional wisdom was that all quant funds had underperformed equally—but a closer look at the data told a very different story.

The lesson our team derives from the history of quant investing is simple: we believe in pairing smart computers with even smarter people.

Human Wisdom, Machine Intelligence

By 2011, the Quant Quake drove Goldman Sachs to close its once-imperious Global Alpha fund. However, it bears noting that Global Alpha was a pure quant fund which operated with limited human intervention. Meanwhile, Goldman’s actively managed quant strategy—called Global Equity Insights with Country Tilts—remained on the shelf because it fared much better in 2007 and again, later on, during the COVID-19 crisis. The same was true of other human-plus-machine funds from independent providers, which, unlike their pure quant counterparts, withstood the test of time.

In the years after the Quant Quake there was a profound reckoning with what went wrong. Across the industry, quant managers re-evaluated the way they saw liquidity, leverage, and crowded trades.9 They increased transparency and showed institutional investors how their fiduciary promise could align with the performance delivered. In other words, they recognized that when markets encounter serious headwinds, experienced investment professionals must take control.

As mentioned at the outset of the article, I held this view very strongly when I joined BMO Global Asset Management—and so did my new team. We all derived a very clear lesson from the history of quant investing: always pair smart computers with even smarter people. We recognized that humans, and only humans, can know a machine’s limitations.

More information, or the ability to process that information, does not automatically make for wiser decisions; you need the proper context. Algorithms may indeed make the investment world easier to understand, but humans are the ones who build the models and write the code, because people should ultimately decide which problems are worth solving.

Please contact your BMO Institutional Sales Partner for additional market insights.

Insights

Sources

1James Owen Weatherall, The Physics of Wall Street; page 102

1James Owen Weatherall, The Physics of Wall Street; page 102

3James Owen Weatherall, The Physics of Wall Street; page 120.

4Parallel Computing, Volume 25, Issues 13-14; Stavros A. Zenios

5Corbin Ball, 1962-2022: A 60-Year Timeline of Events Technology Innovation

6Preqin, Hedge Funds: A Journey Through Time, https://www.preqin.com/academy/lesson-3-hedge-funds/history-of-the-hedge-fund-industry.

4Parallel Computing, Volume 25, Issues 13-14; Stavros A. Zenios

8The Financial Times, Goldman Sachs’ lessons from the ‘quant quake’; March 9, 2017.

9MSCI, Ten Years Later: What We Learned From The Quant Liquidity Crunch; 2017.

Disclaimers

Not intended for distribution outside of Canada.

The viewpoints expressed by the Portfolio Manager represents their assessment of the markets at the time of publication. Those views are subject to change without notice at any time. The information provided herein does not constitute a solicitation of an offer to buy, or an offer to sell securities nor should the information be relied upon as investment advice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. This communication is intended for informational purposes only.

Certain of the products and services offered under the brand name BMO Global Asset Management are designed specifically for various categories of investors in a number of different countries and regions and may not be available to all investors. Products and services are only offered to such investors in those countries and regions in accordance with applicable laws and regulations.

This communication is intended for informational purposes only and is not, and should not be construed as, investment, legal or tax advice to any individual. Particular investments and/or trading strategies should be evaluated relative to each individual’s circumstances. Individuals should seek the advice of professionals, as appropriate, regarding any particular investment. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

All figures and statements are as of month end unless otherwise indicated. Performance is calculated before the deduction of management fees. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The information provided herein does not constitute a solicitation of an offer to buy, or an offer to sell securities nor should the information be relied upon as investment advice. All investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Certain statements included in this material constitute forward-looking statements, including, but not limited to, those identified by the expressions “expect”, “intend”, “will” and similar expressions. The forward-looking statements are not historical facts but reflect BMO AM’s current expectations regarding future results or events. These forward-looking statements are subject to a number of risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results or events to differ materially from current expectations. Although BMO AM believes that the assumptions inherent in the forward-looking statements are reasonable, forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and, accordingly, readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on such statements due to the inherent uncertainty therein. BMO AM undertakes no obligation to update publicly or otherwise revise any forward-looking statement or information whether as a result of new information, future events or other such factors which affect this information, except as required by law.

All Rights Reserved. The information contained herein: (1) is confidential and proprietary to BMO Asset Management Inc. (“BMO AM”); (2) may not be reproduced or distributed without the prior written consent of BMO AM; and (3) has been obtained from third party sources believed to be reliable but which have not been independently verified. BMO AM and its affiliates do not accept any responsibility for any loss or damage that results from this information.

BMO Global Asset Management is a brand name under which BMO Asset Management Inc. and BMO Investments Inc. operate.

®/™Registered trademarks/trademark of Bank of Montreal, used under licence.